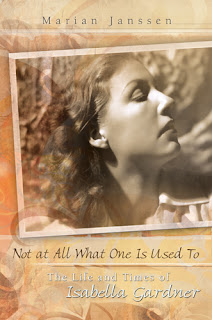

Not at All What One Is Used To by Marian Janssen

Born to an elite family, Isabella Gardner was expected to follow a certain path, but that plan derailed when she caused a drunk-driving accident. Being sent to Europe fanned the romantic longings and artistic impulses that would define her life. She became associate editor of Poetry; poet Allen Tate left his wife to marry her but then abandoned her for a young nun. Gardner associated with many of the most significant cultural figures of her age, but connections couldn’t save her from herself. Her life was emblematic of the cultural unrest at the height of the twentieth century.

It all started in the rare book room of Washington University in St. Louis, where I was doing research for my book on the literary magazine The Kenyon Review. Holly Hall, its librarian, asked me if I would like to see the Isabella Gardner collection there, which no researcher had yet looked at closely. For me, Gardner had been merely one of the few women poets to be published in the male dominated Kenyon Review, but I enthusiastically accepted because nothing is more fun than to see what no one has seen before. Learning from hundreds of letters to Gardner, I realized I had been shamefully inattentive to a poet whose books had been nominated for National Book Awards and the Pulitzer Prize and whom Sylvia Plath saw as a rival to the title of “The Poetess of America.” Yet, when I first made Gardner’s superficial acquaintance, she had been virtually forgotten.

My admiration for her poetry had to overcome my having been steeped in the quasi objective approach to poetry as preached in The Kenyon Review. Gardner’s first collection of poetry, Birthdays from the Ocean, had earned glowing reviews in the 1950s because she had clothed naked feelings of sex, terror, and death in perfectly crafted intense lyric verse, but her other three collections were out of touch with the poetic fashions by which I was swayed. However, being her self-designated biographer I had to immerse myself in her poetry, as even her most distanced poems are very autobiographical, and I was caught. In my book I use snippets of Gardner’s poems because they are the footprints of her life, and I am happy to find that my very first (Kirkus) reviewer is blown away by Gardner’s “stunning” poetry.

Q: How did her poetry figure in Gardner’s life?

When I got acquainted with Gardner in St. Louis, I was struck first by the range of her correspondents in the literary world, from T. S. Eliot to Erica Jong. Also, Gardner called forth inordinate openness in her friends, who told her about their loves and lusts, their marriages and money problems, their ambitions and abortions. But the drama of her life encompassed much more than her being the focal point of an intimate literary circle. Born into one of the first families of Boston, cousin to Robert Lowell, she was a child of wealth who rebelled against her privileged surroundings. Before she became a poet, she was an actress on Broadway; she married into the theater world, then wedded a prominent Russian-Jewish photographer with connections to the mob, who was followed by one of the millionaire Chicago McCormicks; he, subsequently, was cast aside for the southern writer Allen Tate, who then deserted her. During her last years at the Hotel Chelsea in New York she was ravaged by the tragic fates of her wayward children, and struggled with enemies, friends, lovers and the bottle.

Q: As you live in the Netherlands, I suppose your biography is mainly based on published sources?

No way. I have indeed read hundreds of studies dealing with American history and culture, from ballet to business to poetry, and countless biographies, from Elizabeth Bishop to Ernie Kovacs to Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, but they merely firmed up my book’s foundation. I derive my intimate insights from over a hundred interviews and thousands upon thousands of letters, many of them from private collections, most of them never seen by anybody else. In all, I spent two years in America reading Gardner related correspondence in archives and talking to family, friends and acquaintances. They were the best two years of my life.

Q: Why the title Not at All What One Is Used To?

My first choice was Poetry and Passion: The Life and Times of Isabella Gardner, but I decided that title, though fitting, was too static for Gardner’s inordinately tumultuous life. Then my publisher suggested Dead Center of All Alone, a line from one of Gardner’s poems and the title of the tragic last chapter, but this does not do justice to the lust for life that is so very much part of Gardner. Not at All What One Is Used To is the title of a Gardner poem in which she describes her life as an actress, poles apart from her aristocratic background. The title is unexpected, unusual, and as such emblematic of the drama of Gardner’s life.

Q: If you had ever met her, would you have liked her, do you think?

My feelings for Gardner have rollercoasted over the years. A young, impressionable scholar, I started out with admiration for this passionate woman and anger at her being sidelined as a poet in the male-dominated Cold War period. But after I had read the love and hate letters between Gardner and Tate,, I felt she was mired in self-pity. Interviews with people who knew her during her last years and described her as an imperious, nymphomaniacal dipsomaniac increased my moralistic attitude. Then I became an administrator and put Gardner on the backburner for over a decade. Re-reading the letters I had gathered, the interviews I had held when I returned to her after my time-out, my admiration for Gardner came back with a vengeance. Self-pity? Well, perhaps, for a while, but with a philandering husband like Tate she had much reason to. An alcoholic? Yes, but during her last years, she pulled herself together and managed to write some great poems again. I don’t think I have mellowed over the years, but the break has helped me to cut through the surface.

Q: Why should we read this book?

Because it is a super-dramatic, compelling story of a talented actress and most gifted poet, whose kaleidoscopic life under the weight of her aristocratic parentage and wealth, played out in close connectedness with a number of central cultural episodes in America. It is a must for anybody fascinated by American aristocracy and interested in American culture of the twentieth century, from Poetry Magazine to Virgil Thomson, from William Carlos Williams to Yoko Ono, from Cape Cod to Ojai, from the Ballets Russes to the goings-on in the Chelsea Hotel in New York. I share the estimate and confidence of the Kirkus Reviews critic that it is a “long overdue study that will surely spark new interest in Gardner’s work.”

No comments:

Post a Comment